Phishing definition

Phishing is a cyber attack that uses disguised email as a weapon. The goal is to trick the email recipient into believing that the message is something they want or need — a request from their bank, for instance, or a note from someone in their company — and to click a link or download an attachment.

What really distinguishes phishing is the form the message takes: the attackers masquerade as a trusted entity of some kind, often a real or plausibly real person, or a company the victim might do business with. It’s one of the oldest types of cyberattacks, dating back to the 1990s, and it’s still one of the most widespread and pernicious, with phishing messages and techniques becoming increasingly sophisticated.

“Phish” is pronounced just like it’s spelled, which is to say like the word “fish” — the analogy is of an angler throwing a baited hook out there (the phishing email) and hoping you bite. The term arose in the mid-1990s among hackers aiming to trick AOL users into giving up their login information. The “ph” is part of a tradition of whimsical hacker spelling, and was probably influenced by the term “phreaking,” short for “phone phreaking,” an early form of hacking that involved playing sound tones into telephone handsets to get free phone calls.

Nearly a third of all breaches in the past year involved phishing, according to the 2019 Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report. For cyber-espionage attacks, that number jumps to 78%. The worst phishing news for 2019 is that its perpetrators are getting much, much better at it thanks to well-produced, off-the-shelf tools and templates.

Some phishing scams have succeeded well enough to make waves:

What is a phishing kit?

The availability of phishing kits makes it easy for cyber criminals, even those with minimal technical skills, to launch phishing campaigns. A phishing kit bundles phishing website resources and tools that need only be installed on a server. Once installed, all the attacker needs to do is send out emails to potential victims. Phishing kits as well as mailing lists are available on the dark web. A couple of sites, Phishtank and OpenPhish, keep crowd-sourced lists of known phishing kits.

Some phishing kits allow attackers to spoof trusted brands, increasing the chances of someone clicking on a fraudulent link. Akamai’s research provided in its Phishing–Baiting the Hook report found 62 kit variants for Microsoft, 14 for PayPal, seven for DHL, and 11 for Dropbox.

The Duo Labs report, Phish in a Barrel, includes an analysis of phishing kit reuse. Of the 3,200 phishing kits that Duo discovered, 900 (27%) were found on more than one host. That number might actually be higher, however. “Why don’t we see a higher percentage of kit reuse? Perhaps because we were measuring based on the SHA1 hash of the kit contents. A single change to just one file in the kit would appear as two separate kits even when they are otherwise identical,” said Jordan Wright, a senior R&D engineer at Duo and the report’s author.

Analyzing phishing kits allows security teams to track who is using them. “One of the most useful things we can learn from analyzing phishing kits is where credentials are being sent. By tracking email addresses found in phishing kits, we can correlate actors to specific campaigns and even specific kits,” said Wright in the report. “It gets even better. Not only can we see where credentials are sent, but we also see where credentials claim to be sent from. Creators of phishing kits commonly use the ‘From’ header like a signing card, letting us find multiple kits created by the same author.”

Types of phishing

If there’s a common denominator among phishing attacks, it’s the disguise. The attackers spoof their email address so it looks like it’s coming from someone else, set up fake websites that look like ones the victim trusts, and use foreign character sets to disguise URLs.

That said, there are a variety of techniques that fall under the umbrella of phishing. There are a couple of different ways to break attacks down into categories. One is by the purpose of the phishing attempt. Generally, a phishing campaign tries to get the victim to do one of two things:

- Hand over sensitive information. These messages aim to trick the user into revealing important data — often a username and password that the attacker can use to breach a system or account. The classic version of this scam involves sending out an email tailored to look like a message from a major bank; by spamming out the message to millions of people, the attackers ensure that at least some of the recipients will be customers of that bank. The victim clicks on a link in the message and is taken to a malicious site designed to resemble the bank’s webpage, and then hopefully enters their username and password. The attacker can now access the victim’s account.

- Download malware. Like a lot of spam, these types of phishing emails aim to get the victim to infect their own computer with malware. Often the messages are “soft targeted” — they might be sent to an HR staffer with an attachment that purports to be a job seeker’s resume, for instance. These attachments are often .zip files, or Microsoft Office documents with malicious embedded code. The most common form of malicious code is ransomware — in 2017 it was estimated that 93% of phishing emails contained ransomware attachments.

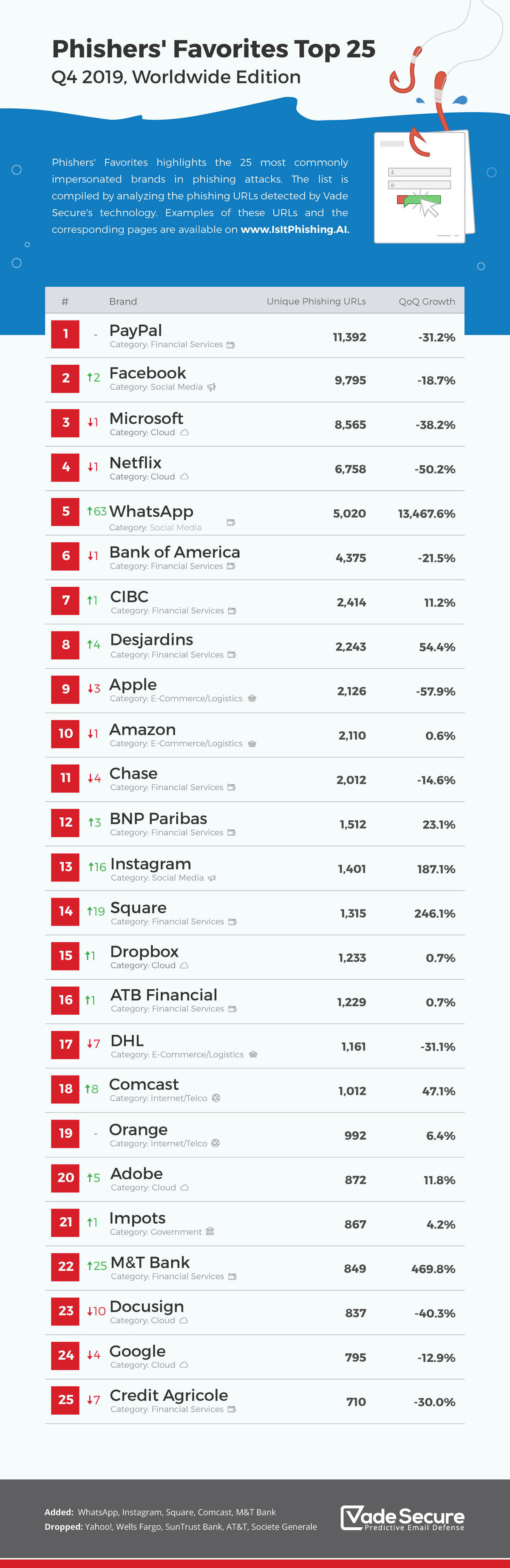

There are also several different ways that phishing emails can be targeted. As we noted, sometimes they aren’t targeted at all; emails are sent to millions of potential victims to try to trick them into logging in to fake versions of very popular websites. Vade Secure has tallied the most popular brands that hackers use in their phishing attempts (see infographic below). Other times, attackers might send “soft targeted” emails at someone playing a particular role in an organization, even if they don’t know anything about them personally.

Vade Secure

Vade SecureBut some phishing attacks aim to get login information from, or infect the computers of, specific people. Attackers dedicate much more energy to tricking those victims, who have been selected because the potential rewards are quite high.

Spear phishing

When attackers try to craft a message to appeal to a specific individual, that’s called spear phishing. (The image is of a fisherman aiming for one specific fish, rather than just casting a baited hook in the water to see who bites.) Phishers identify their targets (sometimes using information on sites like LinkedIn) and use spoofed addresses to send emails that could plausibly look like they’re coming from co-workers. For instance, the spear phisher might target someone in the finance department and pretend to be the victim’s manager requesting a large bank transfer on short notice.

Whaling

Whale phishing, or whaling, is a form of spear phishing aimed at the very big fish — CEOs or other high-value targets. Many of these scams target company board members, who are considered particularly vulnerable: they have a great deal of authority within a company, but since they aren’t full-time employees, they often use personal email addresses for business-related correspondence, which doesn’t have the protections offered by corporate email.

Gathering enough information to trick a really high-value target might take time, but it can have a surprisingly high payoff. In 2008, cybercriminals targeted corporate CEOs with emails that claimed to have FBI subpoenas attached. In fact, they downloaded keyloggers onto the executives’ computers — and the scammers’ success rate was 10%, snagging almost 2,000 victims.

Other types of phishing include clone phishing, vishing, snowshoeing. This article explains the differences between the various types of phishing attacks.

Why phishing increases during a crisis

Criminals rely on deception and creating a sense of urgency to achieve success with their phishing campaigns. Crises such as the coronavirus pandemic give those criminals a big opportunity to lure victims into taking their phishing bait.

During a crisis, people are on edge. They want information and are looking for direction from their employers, the government, and other relevant authorities. An email that appears to be from one of these entities and promises new information or instructs recipients to complete a task quickly will likely receive less scrutiny than prior to the crisis. An impulsive click later, and the victim’s device is infected or account is compromised.

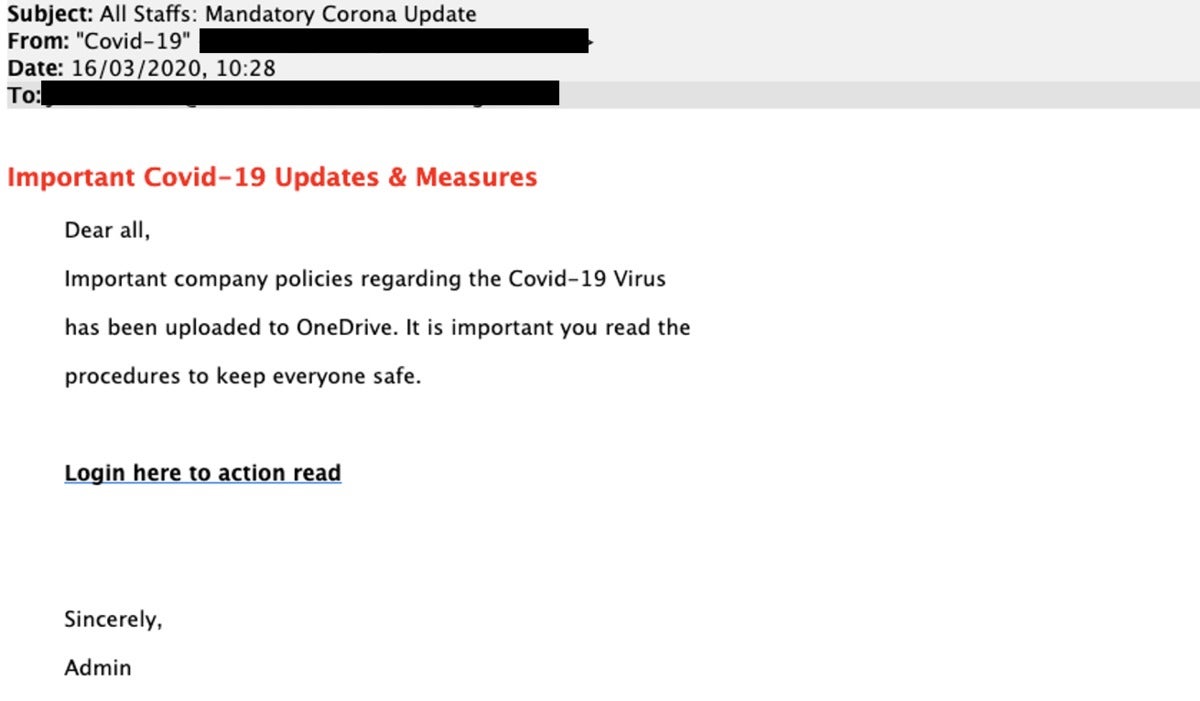

The following screen capture is a phishing campaign discovered by Mimecast that attempts to steal login credentials of the victim’s Microsoft OneDrive account. The attacker knew that with more people working from home, sharing of documents via OneDrive would be common.

Mimecast

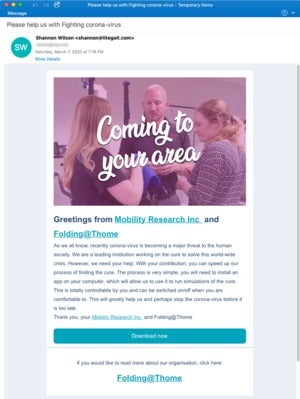

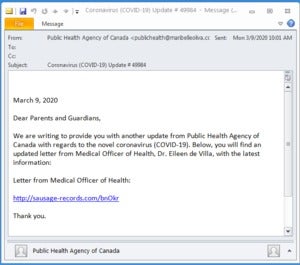

MimecastThe next two screens are from phishing campaigns identified by Proofpoint. The first asks victims to load an app on their device to “run simulations of the cure” for COVID-19. The app, of course, is malware. The second appears to be from Canada’s Public Health Agency and asks recipients to click on a link to read an important letter. The link goes to a malicious document.

Proofpoint

Proofpoint Proofpoint

ProofpointHow to prevent phishing

The best way to learn to spot phishing emails is to study examples captured in the wild! This webinar from Cyren starts with a look at a real live phishing website, masquerading as a PayPal login, tempting victims hand over their credentials. Check out the first minute or so of the video to see the telltale signs of a phishing website.

More examples can be found on a website maintained by Lehigh University’s technology services department where they keep a gallery of recent phishing emails received by students and staff.

[ See 15 real-world phishing examples — and how to recognize them ]

There also are a number of steps you can take and mindsets you should get into that will keep you from becoming a phishing statistic, including:

- Always check the spelling of the URLs in email links before you click or enter sensitive information

- Watch out for URL redirects, where you’re subtly sent to a different website with identical design

- If you receive an email from a source you know but it seems suspicious, contact that source with a new email, rather than just hitting reply

- Don’t post personal data, like your birthday, vacation plans, or your address or phone number, publicly on social media

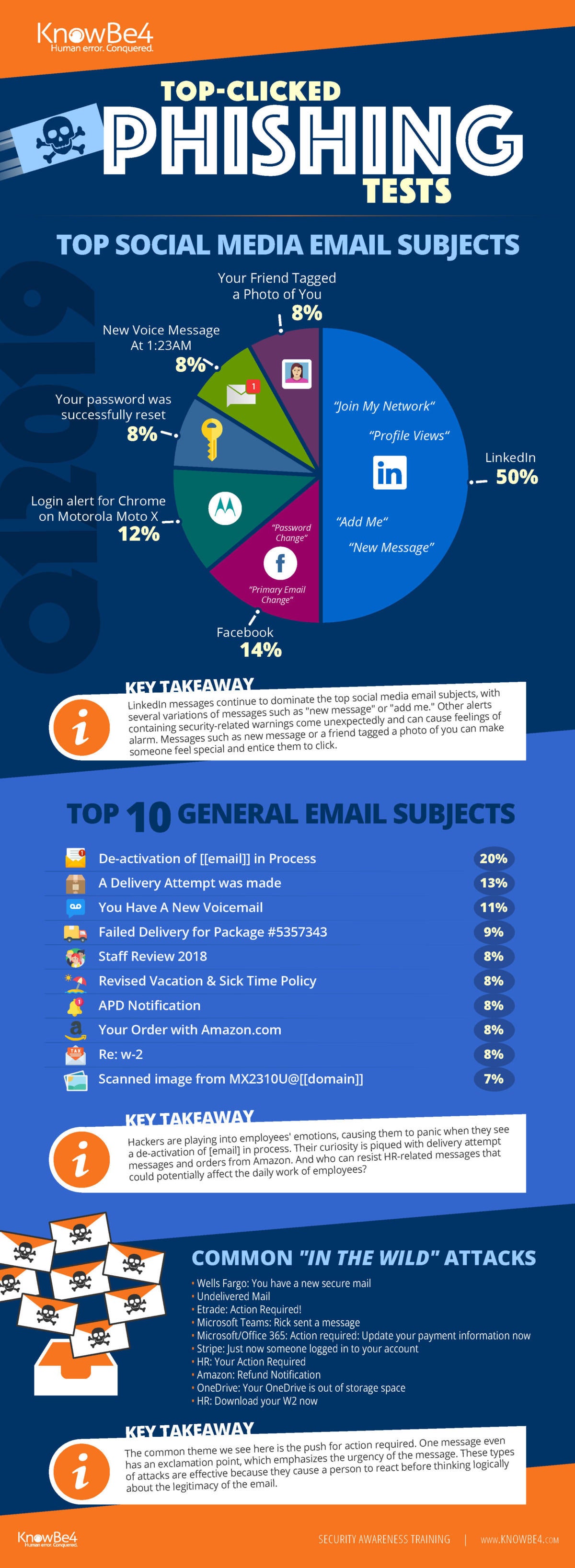

KnowBe4

KnowBe4These are the top-clicked phishing messages according to a Q2 2018 report from security awareness training company KnowBe4

If you work in your company’s IT security department, you can implement proactive measures to protect the organization, including:

- “Sandboxing” inbound email, checking the safety of each link a user clicks

- Inspecting and analyzing web traffic

- Pen-testing your organization to find weak spots and use the results to educate employees

- Rewarding good behavior, perhaps by showcasing a “catch of the day” if someone spots a phishing email

Copyright © 2020 IDG Communications, Inc.

[ad_2]

Article Source link

Is your business effected by a COVID-19 / Coronavirus related Cyber Crime?

If a cyber crime or cyber attack happens to you, you need to respond quickly. Cyber crime in its several formats such as online identity theft, financial fraud, stalking, bullying, hacking, e-mail fraud, email spoofing, invoice fraud, email scams, banking scam, CEO fraud. Cyber fraud can lead to major disruption and financial disasters. Contact Digitpol’s hotlines or respond to us online.

Digitpol is available 24/7.

Email: info@digitpol.com

Europe +31558448040

UK +44 20 8089 9944

ASIA +85239733884